How to Be Funny

Edited 8-21

Edited 8-21Though shy, my husband tells jokes well and is a good speaker. He instinctively gets the pacing right and doesn’t meander. One of his favorite jokes is “Good news/Bad News,” because it can be adapted as a segue into nearly any speech. The basic joke goes as follows:

Two friends John and Dave were two huge baseball fans. Their entire lives, John and Dave talked baseball. They went to 60 games a year. They even agreed that whoever died first would try to come back and tell the other if there was baseball in heaven.

One night, John passed away in his sleep after watching the Yankee victory earlier in the evening. He died happy. A few nights later, his buddy Dave awoke to the sound of John's voice from beyond.

"John is that you?" Dave asked.

"Yes, it's me," John replied.

"This is unbelievable" Dave exclaimed. "So tell me, is there baseball in heaven?"

"Well I have some good news and some bad news for you. Which do you want to hear first?"

"Tell me the good news first."

"Well, the good news is that yes there is baseball in heaven."

"Oh, that is wonderful, So what is the bad news?"

"You're pitching tomorrow night."

What’s funnier, though, is when my husband tries to tell a joke when his mother and brother are present. His brother is profoundly deaf, and my mother-in-law yells each line—but screws it up—as my husband tries to proceed.

For example, if he started with the first line of the joke above: “Two friends John and Dave were two huge baseball fans.”

She would yell, “THERE WERE TWO GUYS – DAVE AND JERRY!”

My husband would say, clearly irritated, “No; that’s not the point! They loved baseball, and they were good friends.”

She would yell, “YEAH, AND THESE TWO GUYS WENT TO BASEBALL GAMES!”

...This would continue until my husband was mad, I was laughing, and the joke was in tatters.

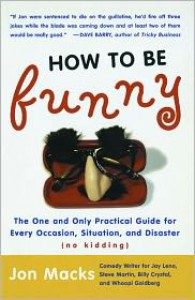

Jon Macks’ book is designed for people who want to inject humor into their everyday conversations. I bought the book because I’m working up a course on humor and thought it might be relevant. However, the book’s premise is interesting. I wonder how well this really works. My husband—who’s already funny—would probably balk at the non-spontaneous nature of much of Macks’ suggestions, such as pre-arranged funny things you can say on an elevator, like “I swear; I’m going to beat this indictment,” or “Is that a chalk body outline in the corner?” My mother-in-law who’s unintentionally hilarious would be unlikely to profit from the book. My own hunch is that you’re either funny or not; using a book like this might just make you both unfunny and obnoxious.

I thought Macks’ style was good—breezy with lots of examples of humor. However, because he wrote for Jay Leno and clearly is chummy with a number of the other comics he mentions frequently—such as Carrie Fisher, Dave Barry, or Rita Rudner—too much of the book comes across as an homage to these comedians. Macks is at his best when he explains and provides examples of the principles of humor. When he tries to invent scenarios in which to use this rather scripted humor, such as in the elevator, when trying to pick someone up, in an argument with your spouse, or in the workplace, the humor and premise get a little strained.

If you want to understand some of the techniques of humor, the book is a quick, light read, though rather scant. However, if humor’s never been your bag, this book isn’t going to turn you into Groucho Marx.