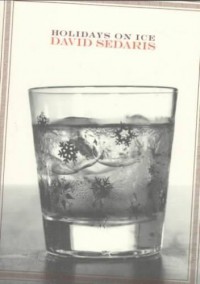

Holidays on Ice

My mother was a little crazy.

She saw people looking through our windows, heard them whispering under our porch, spotted private family conversations in the newspaper, unexpectedly screamed profanity at people who looked suspicious (sometimes while we were in a restaurant or some other very public location), and thought the writing on trucks and other vehicles that passed us on the road were coded messages just for her. … It was a bit creepy.

My father didn’t help. Rather than acknowledging my mother was crazy (she had paranoid schizophrenia, which I didn’t know until my late teens), he said she was “nervous.” This verdict suggested her visions were normal, and to my young mind, validated the notion that there were indeed people peeking into the house. It made me rather skittish.

However, as a bright side to my mother’s fickle mental state, she was brilliant and often savagely funny when lucid. Form letters—letters sent at Christmas generally boasting of a family’s all-around success and wholesomeness—were targets of particular glee. My mother would read these saccharine missives with just the right amount of over-the-top chirpiness, and then would compose her own, much darker, Christmas form letter about our family. For example, “Last summer, mother was institutionalized again at Grover’s Sanitarium. It is a lovely tree-lined facility, and who can forget the shock treatments!? Whee!!!” We had a highly evolved sense of humor. However, even in her darkest moments, I doubt my mother could have matched David Sedaris’ send-up of form letters in his essay, “Season’s Greetings to Our Friends and Family!!!!”

Humor has always been about pushing the envelope. How far can you stretch humor before it tips over the edge and becomes disturbing? There’s no clear answer. I had a friend once comment vigorously, “You think the movie Fargo is funny? That’s not a funny movie!” Well sorry. I think it is. But humor is also deeply idiosyncratic. In Sedaris’s mock form letter, and this is not much of a spoiler given that you know something truly amiss is going on with the Dunbar family early on, the baby grandson is found—lifeless—in the dryer, having died while in the washing machine (but mercifully and most certainly, our letter writer assures us, before the spin cycle)… It’s not an essay that would appeal to everyone.

I doubt few would debate the humor of Sedaris’ classic “Santaland Diaries” or “Jesus Shaves,” which also appears in his collection Me Speak Pretty One Day. Yesterday, I was trying to describe and then read a couple of short excerpts from the latter essay, when I found a YouTube clip of Sedaris reading the essay. Humor is wickedly difficult to write; you’re confined to prose to convey the pacing and intonation comedy requires. And then there’s Sedaris’ voice, slightly nasal, droll, and deliciously snarky. When my husband heard the essay, read by Sedaris, he laughed so hard he had tears running down his cheeks.

“The Cow and the Turkey” is another wonderfully funny essay, slightly reminiscent of James Thurber’s wild fables. There’s no way to convey its humor adequately. Just think of a barnyard, the problems being a Secret Santa might pose for the animals, and a very sinister cow. My mother was that cow, and yes, Moira, I know this has Faulknerian echoes:

“My mother is a fish.”